Cascarilla

Cascarilla (Croton eluteria)

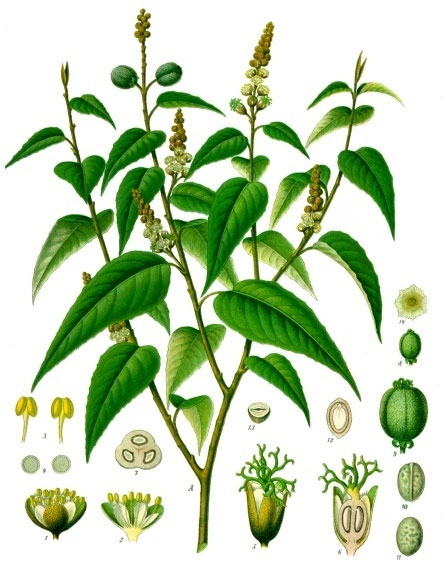

Illustration - Köhlers Medizinal-Pflanzen (1887) (PD)

Cascarilla - Botany

Cascarilla is a relatively small to moderately sized shrub-like tree that was originally native to the Caribbean Islands and its surrounding territories, but has since been naturalised in many other areas across the globe. It originally thrived in the Island of the Bahamas, particularly in Eleutheria (from which one of its many names is derived), but soon spread to various areas, most often by trade or through artificial introduction. Cascarilla is a very common plant in Mexico and other underlying territories, and is a very popular medicinal plant for Hispanic peoples, although this employment may have been strongly influenced by the formerly prolific use of the plant by indigenous cultures such as the Pueblo Peoples, prior to the arrival and eventual colonisation of Mexico and its surrounding areas by the Spanish. Cascarilla is also not unknown to the Ancient Chinese, the Japanese, and the Koreans, as the plant also thrives, albeit in less prolific numbers, in select woodland areas in their respective nations. [1]

The shrub tends to be compact in size if grown for ornamental purposes, although in the wild, it grows to the size of a moderately tall tree, veering anywhere between fifteen to a maximum of twenty feet tall in some very old specimens. It is characterised by the compact growth patterns of its leaves and branches, which tend to grow angularly. The leaves, which are bright-green in colour, is possesses of a downy or scaly growth throughout the obverse and reverse sides, although this down is more predominant on the reverse side, and only mildly visible on the obverse, giving mature leaves a slight greyish tinge. The leaves are also notable for a few choice spots scattered about its surface, which at first appears as leprous spots peculiar to plants with fungal infections. This feature, is, however, natural for the plant itself and is not at all a sign of 'illnesses'. It also sports tiny florets which feature cattail-like growths on the uppermost parts of the plant and normal floret growth in the lower areas. The flowers vary from a pale-yellow to yellow-white hue, and border on the minute. The plant, upon fertilisation, feature slightly roundish seed capsules that house a singular seed per capsule, which pea-sized and replete with furrows.

Cascarilla - History

It is prized for its fragrant flowers when grown ornamentally, but has been harvested or wildcrafted since ancient times for its highly fragrant bark which is harvestable only on very mature specimens. The bark is relatively dark green in hue during the plant's nascence, but later darkens into a pale yellowish-brown. Very old bark features several fissures that are common for the plant, often being home to species of lichen which are oftentimes scraped off upon harvesting and eventual processing, or otherwise left intact if the plant is simply to be employed as incense. [2]

In spite of cascarilla's popularity in Spanish-occupied areas and many other underlying territories, it is no longer as strongly or frequently employed, either in medicine nor in perfumery, as it was some five hundred or so years ago - it's usage primarily declining due to the advent of the Industrial Revolution, and due, in part, to the eventual industrialisation of many rural and formerly mountainous areas where the plant used to thrive. While the leaves are employed ethnobotanically as a medicinal compound, the plant is most commonly harvested for its bark, oftentimes constituting the death of an entire mature plant in some forms of harvesting, in order to maximise yields.

Cascarilla - Herbal Uses

While cascarilla bark is now relatively unknown in the general practice of alternative medicine, it was once commonly employed in both the East and West, chiefly as a tonifying plant. In modern times, the use of cascarilla has become somewhat limited, in part due to the relative obscurity of the plant, which often only features strongly in the tribal applications of it by Mexico's indigenous peoples and other neighbouring tribes, as well as by a few esoterically oriented Chinese and Japanese medicinal applications. The bark was formerly harvested chiefly for its use as a dyeing agent - as it created a wonderful black dye which was not only colour-fast, but possessed superior properties which differed strongly from other dyes of the time, the majority of which was merely very dark blue or very dark brown which took several applications on cloth to achieve a good, solid black hue. Cascarilla's black dye rendered a pure black, which required only very little repeated application, and provided a matte-finish which made it ideal for the dyeing of gabardine, crepe and bombazine - cloths which reached their vogue during the height of the Victorian Era, when the custom and practice of 'English-style' mourning began after the passing of Queen Victoria's husband, Prince-Consort Albert. This created a somewhat sizeable demand for cascarilla bark, although other means of dyeing cloth a matte, full-black had by then already been widely available, cascarilla not being the only means to obtain a pure-black dye. [3]

Outside of its dyeing capacity, it has long been used medicinally as a general tonic, a stomachic, a bittering agent, and as a remedy for various digestive and general complaints. While the bark is the most commonly employed constituent of the plant, the leaves of cascarilla itself has been decocted and drunk as a remedy for indigestion, bloating, colic, lumbago, and dyspepsia. Stronger decoctions of the leaf have been employed as an emmennagogue, although its efficiency for such employment is dubious at best. In Brazil and Mexico, where its usage is more prolific, mild to moderately strong decoctions of the bark have even been employed as a remedy for anaemia, high blood pressure, and a number of urinary complaints. [4]

The bark itself contains several active compounds, and is known for its distinct, earthy, warm scent redolent of a combination of several known warming spices such as cardamom, nutmeg, and clove. When mildly decocted, the ensuing liquid can be drunk to prevent vomiting, to improve digestive function, and to relieve mild to moderate stomach complaints. Being a very bitter draught, it is often drunk as a general tonic and an overall stomachic said to improve nutritional absorption, bile flow, and blood circulation. Strong decoctions of the bark are often given as a remedy for fevers, as it is believed to be an excellent febrifuge. Because of its superior, warming scent, it has even been employed as a fumigating agent to help remedy a number of bronchial and nasal disorders ranging from stuffy nose, asthma, dry cough, and wheezing. [5] The whole bark can be employed as an inhalant, either by throwing broken pieces of it into hot water, or by scattering tiny shavings of the dried bark over hot coals. Inhaling the smoke exuded may help to relieve the symptoms of bronchitis and improve the overall condition of an individual who suffers from asthma, although frequent or prolonged use may have minor detrimental effects. [6]

Because of its wonderfully unique aroma and its mild decongestant effects, shavings of the bark were often integrated into tobacco mixtures - a practice which is quite common both in the local employment of tobacco in Mexico and the Bahamas, as well as a wider range of consumption throughout much of the Western world, particularly in some areas of the Southern United States, as well a small body of European countries. The practice was considered as decidedly rustic, albeit it imparted a wonderful angle of body and aroma, especially to Oriental blends. The practice is still done today, albeit only rarely, as it has a tendency to cause headaches, nausea, and vomiting when partaken of in copious amounts. [7]

When steeped in diluted alcohol, the bark can be made into a tincture and given (in diluted amounts) as a remedy for cough, moderate stomach ailments, and various feminine complaints, although care should be taken in its consumption as alcoholic extracts of the bark tend to possess more side effects than any other preparation. [8]

The bark is also a prime source of a potent essential oil which can be obtained from the raw material through standardised stream distillation. This essential oil, which is noted for its warm, spicy notes, is employed, albeit rarely, in perfumery and aromatherapy, with a scent that can be best described as a mixture of nutmeg, cloves, and cardamom (sometimes with a hint of musk). It has traditionally been mixed with one's choice of base oil to create an excellent salve that helps to relieve chest pains, bronchitis, and general aches and pains. When diffused in hot water or otherwise employed via a diffuser, it can be used as a remedy for asthma and whooping cough in the same light as the burnt bark. [9]

Cascarilla - Esoteric Uses

In spite of the relatively popular employment of cascarilla in Mexico and its neighbouring areas, which are known for their deep-seated practice of magick, there is almost no known esoteric use for the plant. There is, however, a substance similarly named [10] which is derived from ground and pulverised eggshells, which are employed for casting, warding, and as an ingredient in some forms of conjure. This type of cascarilla, commonly employed in Santeria, Candomble, voodoo and Hoodoo, is, however, wholly unrelated to cascarilla the plant, and contains nary a trace of Croton eluteria.

Cascarilla - Contraindications And Safety

While the internal consumption of cascarilla bark is considered relatively safe, prolonged or copious intake of the plant matter is not advised, as it can result in dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and stomach upset. Likewise, the integration of the dried bark to tobacco mixtures are deemed relatively safe if consumed in moderate amounts, however regular consumption may result in nausea and dizziness. As a general safety-note cascarilla should not be given to children below the age of eight, nor to pregnant and nursing women. The internal intake of cascarilla, whether through decocted preparations or via inhalation, should not exceed a week at best, and only in mild to moderate dosages.

Cascarilla - Other Names, Past and Present

Chinese: guimo

Japanese: sukeru

Korean: gyumo

Thai: khnad

Malay: skala (derived from the Spanish cascarilla)

French: eschelle / cascarille

Spanish: cascarilla (lit. 'little bark') / carcanapire / chacarilla / quina aromatica

Portuguese: escala

Italian: cascarilla

German: maflstab / kaskarillbaum

English: sweet bark / sweet wood bark / cascarilla (adopted from the Spanish) / eleutheria (its common name in the Bahamas) /

Bahama cascarilla (employed for a specific species of the plant which thrives in the Bahamas, considered among the most superior

varieties for medicinal and aromatherapeutic usage)

Latin (scientific nomenclature): Croton eluteria / China nova (former nomenclature, now defunct) / Cascarillae

cortex / Cortex eluteriae / Cortex thuris

References:

[1 - 2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Croton_eluteria

[3] https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/c/cascar28.html

[4] https://www.rain-tree.com/cascarilla.htm#.UzldY7VNQm-

[6][7][8] https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/kings/croton-elut.html

[9] https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=A0Hz98Kwp9kC&pg=PA256

[10] https://themagickinyoursoul.wordpress.com/2011/04/06/cascarilla-protection-purification-cleansing/

Main article researched and created by Alexander Leonhardt.

© herbshealthhappiness.com

1. Famous Chef Sheds 60lbs Researching New Paleo Recipes: Get The Cookbook FREE Here

2. #1 muscle that eliminates joint and back pain, anxiety and looking fat

3. Drink THIS first thing in the morning (3 major benefits)

4. [PROOF] Reverse Diabetes with a "Pancreas Jumpstart"

5. Why Some People LOOK Fat that Aren't

6. Amazing Secret Techniques To Protect Your Home From Thieves, Looters And Thugs

7. The #1 WORST food that CAUSES Faster Aging (beware -- Are you eating this?)

If you enjoyed this page: