Juniper

Juniper Uses and Benefits - image to repin / share

Infographic: herbshealthhappiness.com. Image credits: See foot of article

Juniper - Botany And History

Junipers are relatively large evergreen plants of the genus Juniperus, of which more than fifty species exist through the world. Initially classified as either Old World or New World species, these hardy and flourishing coniferous plant have been employed for a variety of different purposes since ancient times. Junipers usually grow from between twenty to forty metres in length, although smaller specimens exist both in nature and artificially (as in the case of juniper bonsais). It is typified by its shrublike body (in small to medium-sized specimens) and long trailing branches which are more pronounced in larger or older specimens. Junipers are mostly noticeable for their needle-like or scale-like foliage (these typically vary depending on the species of juniper), and for their oftentimes scaly or flaky bark. Junipers are also noticeable for their berry-like seed cones which are actually two fleshy scale that meld together to form a single "fruit". While the leaves of mature junipers are themselves not edible, its fruit or berry has been employed by various cultures as a foodstuff when relatively fresh, or as a type of spice when hard and dry. Because of the diverse types of junipers all over the world, no two plants possess the exact same characteristics, although they possess relatively the same medicinal properties and flavour profiles. Being an ancient species of tree, juniper has been employed throughout nearly all cultures as either a foodstuff or a medicinal plant. [1]

It should be noted that junipers, being evergreen trees, possess similar characteristics to coniferous or evergreen plants such as yews and cypresses, which are, in some cases, a distant cousin of the genus Juniperus. Because of this, junipers are typically identified while still in a juvenile state, as it possesses distinct qualities which cannot be found in any other evergreen species (with a given number of qualities which it shares in similarity with other evergreen plants). Juvenile junipers tend to possesses prickly leaves and stems which can be quite difficult to handle barehanded, while their stems and as-yet underdeveloped bark lacks the joints or growth 'knobs' found on older specimens. When compared to other evergreens, such features are altogether absent, allowing for the easier identification of junipers contra other similarly-shaped or closely-related species. [2]

Juniper - Herbal Uses

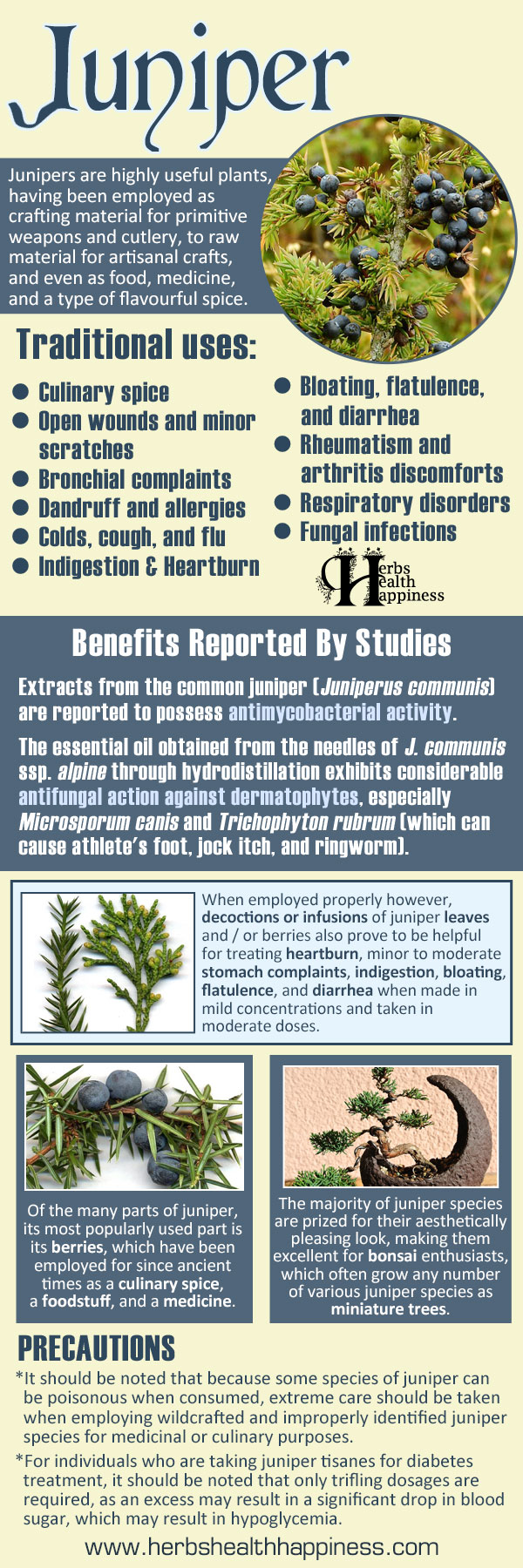

Juniper is among the most widely-used trees in the whole of human history, with various primitive cultures having employed it for culinary, practical, medicinal, or gustatory purposes since prehistoric times. Junipers are highly useful plants, having been employed as crafting material for primitive weapons and cutlery, to raw material for artisanal crafts, and even as food, medicine, and a type of flavourful spice. Nowadays, the use of juniper has become somewhat limited to the aesthetic, with small or juvenile specimens typically being used as prime candidates for bonsai training - a practice which hearkens back to the early Chinese and (later) Japanese cultures, or as a prime choice for landscaping purposes due to their pleasant-looking foliage, fresh aroma, and hardy nature. Aside from its role in the decorative and artistic horticultural world, juniper wood is also employed as lumber both for construction and as a source of fuel - a practice which has remained constant since it was first used for such purposes during ancient times.

The majority of juniper species are prized for their aesthetically pleasing look, making them excellent for bonsai enthusiasts, which often grow any number of various juniper species as miniature trees. In some parts of the globe, juniper continues to be used as a primary source of fuel for cooking, curing, and other practical purposes. Being somewhat resinous while still in its semi-mature state, it can be employed as a basic source of wood for smoking and curing meats, imparting unto the foodstuff a distinct type of flavour which is said to work best with pork, and some types of robust fishes such as trout and tuna. [3] Because juniper branches tend to impart its resins unto the foodstuffs, they can be very flavourful, thus necessitating spare usage.

Juniper wood which has been allowed to dry in the sun, or otherwise aged through other mediums soon loses its resinous or 'sappy' quality, and becomes an excellent wood for crafting various rudimentary tools (as was the case during ancient times), practical items, and even artisanal objets d'art, however, since curing or aging juniper can be a laborious process, it is often employed chiefly for more expensive objects, whether it be decorative (i. e. carvings, statuettes) or practical (i. e. furniture, wooden cutlery, personal effects). Old juniper wood takes on a mellow, fleshy or dun-coloured hue, and when polished to beautiful sheen is perfect for either interior or exterior décor. In some instances, juniper wood is often classified or referred to 'cedar wood' in furniture-making circles, perhaps due to its close resemblance to true cedar (the latter of which can be quite pricey). An interesting feature of furniture made with juniper wood is that they resist attacks by most common borers and other pests (i. e. moth larvae, roaches, etc.), mainly due to their inherent 'insecticidal' properties, which are retained long after the wood has aged and significantly dried. [4] This 'feature' however is only present in untreated examples, as waxing, oiling, or varnishing the articles will nullify its insecticidal properties.

When employed for culinary purposes, the leaves of the juniper plant may be employed to impart a distinctly unique flavour to fish or meats (akin to the flavour imparted by smoking foodstuffs with small amounts of its branches or bark). The leaves may be gently rubbed unto one's choice of foodstuff prior to grilling to add a fresh, zingy flavour which works best when combined with herbs such as basil, sage, or rosemary. Some juvenile juniper species may possess edible leaves which can be lightly blanched or otherwise integrated into seafood or gamey meats as a type of seasoning herb, although it must be noted that correct and proper identification of the juniper specie is a must as a large body of junipers can be poisonous when consumed even in trifling amounts. Furthermore, many poisonous evergreen plants that bear a close resemblance to juniper can be mistaken as an edible juniper species, thereby causing accidental poisoning when consumed. Of the more than fifty species of juniper, only a handful possess edible leaves - among the few being Juniperus drupacea (Syrian juniper), Juniperus californica (California juniper), and Juniperus oxycedrus (prickly juniper). Since a number of different juniper species exist all throughout the world, at least one or two regional species possess a degree of edibility, with either its leaves and / or its berries being fit for human (and animal) consumption without any degree of potential toxicity. [5] Aside from its edibility, some types of juniper leaves may be employed medicinally, either in fresh or dried form, as it possesses potent diuretic and mild tonifying capabilities. When dried and infused into a tisane, a select number of (non-poisonous) juniper leaves may be given as a mild diuretic as well as a general tonic for the kidneys and the liver. Drunk in minute to moderate dosages daily, it can help to flush out toxins from the body, as well as to encourage the easier flow of urine - a feature which can be extremely helpful for individuals who experience water retention, or for individuals who are on a bodily cleansing routine. Due to the fact that it can be a very potent diuretic, care should be taken when consuming it in very large amounts, as it can cause dehydration when drunk with impunity. It is also due to its relative potency that decoctions of juniper were (and still are believed to be) powerful enough to dissolve kidney stones when drunk on a regular basis. Traditional Chinese Medicine prescribes juniper berries for any and all urinary complaints and all afflictions of the middle to lower abdomen, as it is believed to be nutritive for the spleen, lung and heart. Dried juniper berries were ascribed yang or warming properties which helped to expel 'cold', facilitate in detoxification, aid in digestion, and improve nutrient assimilation. However, prolonged and excessive consumption of juniper-leaf infusions or decoctions may also tax the liver or the kidney, resulting in dangerous complications in the long run.

Of the many parts of juniper, its most popularly used part is its berries, which have been employed for since ancient times as a culinary spice, a foodstuff, and a medicine. Raw, ripe juniper berries (of the nontoxic variety) have long been harvested by the natives of many countries a low-calorie, nourishing foodstuff, typically eaten during times of drought or famine, or otherwise incorporated into a general diet quite common for hunter-gatherer or forager societies. The berries, usually harvested while nearing its peak ripeness, may also be dried for long-term storage and incorporated into stews and soups as an additive, or otherwise finely ground and mixed with other foodstuffs to improve the nutritional profile of a meal, or to impart a distinct flavour to the chosen food. Once employed as emergency rations, especially by Native Americans, the dried juniper berries soon became a staple of frontier survival food - typically mixed with cured or jerked meats. In modern applications, juniper berries are usually more well-known for their integral role in the flavouring of the alcoholic beverage gin, a name which is ironically derived from the Dutch word for juniper - jenever. [6] Initially made for medicinal purposes, it soon became a staple of gin-making, with the alcoholic beverage becoming synonymous with the unique flavour profile associated with juniper berries - so much so that nearly all varieties of gin nowadays come flavoured with authentic or imitative juniper-flavourings.

Outside of its culinary employment, juniper berries have also been consumed as a type of quid by some Native American Peoples due to its potent antibacterial and antimicrobial properties - a practice which has been copied by pioneering settlers who adapted the habits and bush-knowledge of natives. It is this same potent antibacterial property that made juniper an immensely invaluable herb in Mediaeval herbalism. The berries were often kept in the mouth to act as an antiseptic, or otherwise strongly decocted in water to be used as antiseptic rinses for wounds, and even as medicated formulae for bandages. A decoction of juniper berries were applied topically to open wounds, minor scratches, fungal infections and a variety of other skin disorders to hasten healing and prevent infection - a practice which persisted up until the frontier days until well into the heyday of the Wild West. In Native American folkloric medicine, potent decoctions of juniper berries, often intermixed with its roots or its needles were drunk in minute amounts by women as a type of early contraceptive, emmenagogue and abortifacient. It was also applied topically to the scalp and the skin to help counteract dandruff and to cure allergies. A tea made from a mild infusion of juniper berries was drunk by both Native Americans and early settlers as a remedy for colds, cough, flu, and other bronchial complaints [7] - a practice which would later find extensive (read abusive) employment in a large part of Great Britain during the height of the 'gin craze' of the early Victorian to latter Edwardian eras, where heated gin, or gin-and-tonic became a regular (albeit ineffective, and, consequently, eventually harmful) 'cure-all' and 'pick-me-up' for the lower classes. When employed properly however, decoctions or infusions of juniper leaves and / or berries also prove to be helpful for treating heartburn, minor to moderate stomach complaints, indigestion, bloating, flatulence, and diarrhea when made in mild concentrations and taken in moderate doses. Strong decoctions of the leaves or berries, when drunk sparingly, may also help to lower blood sugar serum levels in diabetic patients, although its efficiency is still hotly debated. [8]

When allowed to steep in oil, especially when combined with its roots and inner bark, it made for a perfect ointment that helped to soothe swelling and relieve the discomforts brought about by rheumatism or arthritis. When allowed to steep in alcohol and subsequently mixed with one's choice of base oil, a potent liniment employed for the same purposes was obtainable. [9] Juniper berries have also been employed by many tribal cultures (and even some frontiersmen) as a smokable herb. Native Americans often smoked dried juniper leaves, dried inner bark, or dried and thinly sliced berries, often mixed with wild tobacco or some other locally smokable herb - a practice which was later adopted by the settlers. Smoking juniper, especially juniper berries helped to decongest the lungs and treat mild to moderate cases of asthma, as well as a number of other respiratory disorders. The dried leaves and berries were also burnt in woodfires or thrown unto live embers as an early type of disinfectant 'incense'-cumvapourizer that not only drove away pests, but helped to stave off airborne pathogens - a practice which was commonplace in Pre-Roman Britain, Mediaeval Europe, the Native Americas, Imperial China, and Imperial Japan, just as it was commonplace in Ancient Egypt, pre-Judaic Israel, and Mesopotamia. [10]

The essential oil of juniper is employed, mainly for artisanal brewing, as it is typically added to gin, or otherwise incorporated into a number of other alcoholic beverages for its unique flavour and its attributed medicinal properties. Its essential oil may also be combined with a base oil (with the use of the former being only in absolutely minute amounts) to create an excellent ointment for general aches and pains, as well as for the treatment of a variety of different fungal infections and (traditionally) even gout. When diluted in water (again, using only very minute amounts), the resulting combination yields a potent disinfectant. When employed in aromatherapy, it can help to soothe the nerves and relieve stress. It may even help to wean a person off on an addition, or relieve agitation caused by overthinking or highly stressful environments. It should be noted that juniper's essential oil is a well-known irritant, requiring patch-tests and ample dilution prior to being employed topically. Juniper essential oil is also toxic, requiring careful dosage when taken internally. [11] Juniper oil should never be used in large amounts either externally or internally, nor should it be employed undiluted for whatever purpose other than vapourization for aromatherapeutic purposes.

Juniper - Scientific Studies And Research

The ethnopharmacological use of juniper for its medicinal properties has been relatively well studied. Extracts from the common juniper (Juniperus communis) are reported to possess antimycobacterial activity, especially the aerial parts, and juniper owes this property to its isocupressic acid, communic acid, and deoxypodophyllotoxin content. Carpenter et al. (2012) showed that isocupressic acid and communic acid in juniper have a minimum inhibitory concentration of 78 μM and 31 μM and an IC50 value of 46 μM and 15 μM against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra, respectively, whereas deoxypodophyllotoxin has a minimum inhibitory concentration of 1004 μM and an IC50 value of 287 μM, indicating the latter's being less active when compared to the first two. [12] The findings from Carpenter et al.'s (2012) study are in keeping with those of Gordien, Gray, Franzblau, and Seidel (2009), who attributed the antimycobacterial property of juniper aerial parts and roots however to the presence of longifolene (a sesquiterpene) and totarol and trans-communic acid (diterpenes) in them. In this study, significant results are as follows:

• Totarol displayed the "best activity" against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H(37)Rv at a minimum inhibitory concentration of 73.7 μM and was most active against isoniazid-, streptomycin-, and moxifloxacin-resistant variants. Moreover, it exhibited good and remarkable activity in the low-oxygen-recovery assay and was most particularly active against Mycobacterium aurum, M. phlei, M. fortuitum, and M. smegmatis at minimum inhibitory concentrations of 7-14 μM.

• Both longifolene and totarol were active against the rifampicin-resistant variant at a minimum inhibitory concentration of 24 and 20.2 μM, respectively.

• trans-Communic acid possesses good activity against M. aurum at a minimum inhibitory concentration of 13.2 μM. [13]

The essential oil obtained from the needles of J. communis ssp. alpine through hydrodistillation exhibits considerable antifungal action against dermatophytes, especially Microsporum canis (which causes tinea capitis in humans) and Trichophyton rubrum (which can cause athlete's foot, jock itch, and ringworm). [14]

Treatment using dried berries of juniper had also been reported to slow down the development of diabetes experimentally induced by streptozotocin in mice, particularly decreasing the degree of hyperglycemia in the experimental animals. [15] S·nchez de Medina et al. (1994) had illustrated in detail the hypoglycemic activity of juniper berry decoction in both normoglycemic rats and rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes: at a dose of 250 mg/kg, a substantial decrease in glycemic levels was noted in normoglycemic rats, whereas at a decoction dose of 25 mg total "berries"/kg for 24 days, a decrease in blood glucose levels and mortality index and an absence of body weight loss were recorded in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. [16]

Juniper - Phytochemistry / Active Components

As analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), the primary active constituents of juniper are α-pinene, β-pinene, δ-3-carene, sabinene, myrcene, β-phellandrene, limonene, and D-germacrene. [17] Based on the results of a study using headspace solid phase microextraction with enantioselective GC-MS, the needles and berries of Juniperus communis were determined to contain high contents of sabinene (19-30%), α-pinene (12-24%), and β- myrcene (9-20%). [18] Neolignan glycosides, including junipercomnosides A and B, and flavonoid glycosides were also isolated in another study from the aerial parts of Juniperus communis var. depressa. [19]

Juniper - Esoteric Uses

Juniper has a long history of occultic usage, especially for certain magickal practices endemic to the European world, more specifically in the Germanic and Nordic areas of that part of the country. In Western magick, juniper is considered a protective herb, its leaves being said to possess the capability to drive away bad luck and protect its bearer from all any type of malignancy. In folkloric beliefs, the leaves or needles of juniper trees were typically made into a wreath or a sort of decorative ornament and hung above doorways or above the rafters, as it was said to protect the inhabitants of a house from bad luck, sickness, evil spirits, and the possibility of theft. Wearing a sprig of juniper needles encased in a medicine bag was believed by some Nordic and Icelandic tribes to protect the bearer from attacks by wild animals while subsequently improving their ability to hunt properly, making it a very common item on a primitive hunter's magickal repertoire. [12] The leaves of the juniper plant have long been associated with fortune and profits in the Western branch of sympathetic magick, while in the East it has long been associated with purification or cleansing, as well as facilitating harmony.

The berries of the plant itself, when dried were typically carried as protective amulets, either encased in a drawstring pouch or a leather pouch carried close to one's person. Dried berries have even been bored in the middle and strung together to make beads, which were worn in like manner to the mala prayer beads of India. It was believed to not only protect the bearer from accidents, but that it also increased the wearer's charisma or charm. Juniper berries were often ground up into powder and mixed with love philtres or potions in the belief that it enhanced male potency and improved sexual vigour. [13]

Perhaps the most notable use of juniper in the esoteric sphere of things is in its near indispensable use as incense. Long employed by many primitive cultures in both the East and West as a purifying incense, it is most commonly associated with shamanic practices, more specifically Druidic or Native American shamanic practices, as they employ the herb extensively in smudging. The smoke from incense made from, or containing juniper leaves or berries was said to not only effectively cleanse an area or a person of negativity, but that it also drove away misfortune and evil entities. Because of this association, incense made from juniper leaves, or smoking mixtures containing leaves, inner bark, or shredded dried berries were - and still are employed in many shamanic 'exorcism' rituals. Its ability to drive away evil also played an integral role in its having been employed by Irish, Scottish, and Nordic peoples as an early type of fumigator which, when applied near a sick person's body, was said to hasten healing and markedly improve recovery. [14] In some Native American shamanic practices, juniper is decocted into a potent brew, or otherwise burnt as an incense to ritually cleanse or dedicate items that are to be employed for spellwork, while ceremonial branches of magick employ juniper chiefly as a choice addition for warding and banishing incenses.

Juniper - Contraindications And Safety

It should be noted that because some species of juniper can be poisonous when consumed, extreme care should be taken when employing wildcrafted and improperly identified juniper species for medicinal or culinary purposes. Edible juniper species may likewise contain high concentrations of possible allergens or toxins to highly sensitive individuals, requiring proper dosing and moderated usage. Because of its powerful diuretic and emmenagogue properties, pregnant women should not consume any substance containing juniper, even in minute amounts, since it may cause premature uterine contractions that may result in abortion; so too nursing women should avoid the consumption or liberal usage of any products containing juniper, as it may cause certain reactions that may pose a risk to the infant's development.

For individuals who are taking juniper tisanes for diabetes treatment, it should be noted that only trifling dosages are required, as an excess may result in a significant drop in blood sugar, which may result in hypoglycemia. Individuals who are taking anti-diabetic drugs or diuretic drugs should likewise shy away from using juniper as a 'supplementary' cure, as it may interact with the present medication and cause complications.

Liniments or ointments made from its essential oil or an infusion of its roots, leaves, bark, or berry may cause mild to moderately severe reactions in individuals with very sensitive skin, although it is relatively safe for use in small areas provided that a patch-test is performed first prior to application. Prolonged intake of large amounts of products containing juniper may eventually cause renal damage, seizures, recurring headaches, nausea, and even alarming skin allergies, so extreme caution should be taken when consuming juniper for long periods of time. It is best that one consult with their personal health care expert or an expert herbalist prior to self-medicating or employing juniper for long-term complimentary or alternative medicinal use.

Juniper - Other Names, Past and Present

Chinese: du song / dusongzi

Japanese: byakushin

Korean: hyangnamu

Malay: jintan saru

French: genevrier / genievre

Italian: ginepro

Spanish: enebro / ginebra

Dutch: jenever

German: gemeiner wacholder / wacholderbeeren

Filipino: ginebra (adapted from Spanish) / dyuniper (transliteration of "juniper")

Latin (scientific): Juniperus communis / Juniperus chinensis (other nomenclatures exist depending upon the species)

References:

[1 - 2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juniper

[4] https://juniper.oregonstate.edu/bibliography/documents/php4JjZLY_adams3.pdf

[5] https://www.eattheweeds.com/junipers/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juniper_berry

[7] https://arcticrose.wordpress.com/2008/03/19/juniper-berries-traditional-medicine-or-food-use/

[8 - 9] https://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/j/junipe11.html

[10] https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=71uJKgz7C58C&pg=PA146

[11] https://www.essentialoils.co.za/essential-oils/juniper-berry.htm

[12] Carpenter C. D. et al. (2012). Anti-mycobacterial natural products from the Canadian medicinal plant Juniperus communis, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 143(2): 695-700. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.035. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22877928

[13] Gordien A. Y., Gray A. I., Franzblau S. G., & Seidel V. (2009). Antimycobacterial terpenoids from Juniperus communis L. (Cuppressaceae). Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 126(3): 500- 505. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.007. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19755141

[14] Cabral C. et al. (2012).Essential oil of Juniperus communis subsp. alpine (Suter) Celak needles: chemical composition, antifungal activity and cytotoxicity. Phytotherapy Research, 26(9): 1352-1357. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3730. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22294341

[15] Swanston-Flatt S. K., Day C., Bailey C. J., & Flatt P. R. (1990). Traditional plant treatments for diabetes. Studies in normal and streptozotocin diabetic mice. Diabetologia, 33(8): 462-464. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2210118

[16] S·nchez de Medina F. et al. (1994). Hypoglycemic activity of juniper "berries." Planta Medica, 60(3): 197-200. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8073081

[17] Angioni A., Barra A., Russo M. T., Coroneo V., Dessi S., & Cabras P. (2003).Chemical composition of the essential oils of Juniperus from ripe and unripe berries and leaves and their antimicrobial activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 51(10): 3073-3078. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12720394

[18] Foudil-Cherif Y. & Yassaa N. (2012). Enantiomeric and non-enantiomeric monoterpenes of Juniperus communis L. and Juniperus oxycedrus needles and berries determined by HSSPME and enantioselective GC/MS. Food Chemistry, 135(3): 1796-1800. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.073. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814612010461

[19] Nakanishi T. et al. (2004). Neolignan and flavonoid glycosides in Juniperus communis var. depressa. Phytochemistry, 65(2): 207-213. Retrieved 27 March 2013 from https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/14732280

[20] https://lionheartrealm.blogspot.com/2012/09/herb-of-month-junipercedar.html

[21] https://suite101.com/article/magickal-herbs---the-uses-of-juniper-a338960

Main article researched and created by Alexander Leonhardt.

© herbshealthhappiness.com

Infographic Image Sources:

Pixabay (PD)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Juniperus_communis_cones.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Jun_chin_close.jpg

(Creative Commons)

1. Famous Chef Sheds 60lbs Researching New Paleo Recipes: Get The Cookbook FREE Here

2. #1 muscle that eliminates joint and back pain, anxiety and looking fat

3. Drink THIS first thing in the morning (3 major benefits)

4. [PROOF] Reverse Diabetes with a "Pancreas Jumpstart"

5. Why Some People LOOK Fat that Aren't

6. Amazing Secret Techniques To Protect Your Home From Thieves, Looters And Thugs

7. The #1 WORST food that CAUSES Faster Aging (beware -- Are you eating this?)

If you enjoyed this page: