Seaweed (Edible Varieties)

Seaweed Uses and Benefits - image to repin / share

Infographic: herbshealthhappiness.com. Image credits: See foot of article

Note: For the purposes of this article, only the most popular (current) seaweed varieties and their respective purposes, or a brief overview of such, shall be discussed, in part due to the large body of information regarding various seaweed varieties which, if written down, would be several articles long.

Seaweed - Botany And History

Seaweeds have long been employed for various purposes, although one of its most long-standing primary uses is as food. Seaweed is a popular food item in coastal areas where access to the ocean is readily available, although some societies and cultures that are relatively land-locked but that have access to rivers or lake may have even cultured seaweed or otherwise traded for it for consumption. In areas where there is a ready access to the ocean, seaweed has become something of a culinary staple. In places such as the Mediterranean, but more so in Asia (specifically China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines), the consumption of seaweed as well as its production is among the most profitable of industries.

Seaweeds are not plants per se, as they are common thought of, but are rather comprised of any one of two to three distinct types - either a composition of marine algae from any of the differing families of brown (Phaeophyceae, green (Chlorophyta / Charophyta / Embryophyta), or red (Rhodophyta) marine algae, a collection of edible fungi that has had symbiosis with any of the three algal families, or is the simple excreta or offspring of any small, low-tier marine animal that houses alga or bacteria thought to be traditionally edible. The latter two does not necessarily count as a true and exact definition of 'seaweed' (as only the earliest description is accepted as such scientifically), but it does present some of the lesser-known or less popular sources for 'seaweeds' that are considered mainstays or staples of the food-type and is worth mentioning. It is worth noting that seaweeds, being a type of algae, do not all grow or are sourced from the sea per-se, but some are obtained from any body of water, whether lakes, ponds, or rivers, provided that it is deep enough and possesses the right qualities to facilitate the growth of algae. [1] They comprise a large body of various plant or plant-like species that differ in shape, size, habitat, and taste.

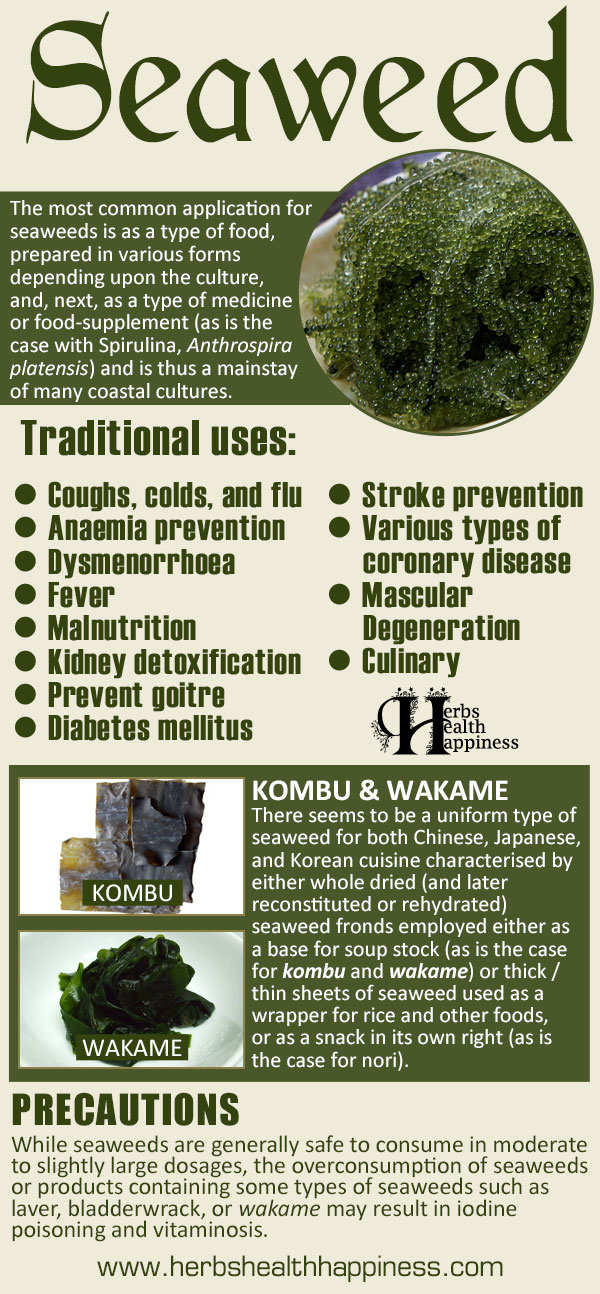

Seaweeds have had a long history of wildcrafting and eventual cultivation, and have been used for everything from food, to medicine, and even as a means of aesthetics or (fairly recently) as natural filtration systems. The most common application for seaweeds is as a type of food, prepared in various forms depending upon the culture, and, next, as a type of medicine or food-supplement and is thus a mainstay of many a coastal culture. Seaweeds are considered among the earliest sources of saltiness, long before various societies conducted trade in, or discovered the means to obtain salt. All forms of seaweed from ancient times were obtained as per availability or 'season' in the wild, although more modern practices have developed the means to culture seaweeds, thereby ensuring constant availability, uniformity of the 'culture' and a guarantee of safety from possible and inevitable contaminants which, prior to the advent of seaweed 'farming' was a very real threat to consumers who had no inkling of the exact origins of their prized provision. [2]

While seaweeds have been consumed by nearly every sea-faring or coastal societal group or culture across history, it is still commonly thought of today to be the general fare of peoples from the Asiatic sphere of the world, thanks in part due to the avidity of seaweed consumption in those cultures or countries. When individuals today mention seaweed, the most common thought that comes to mind is Japanese cuisine, which is truly evidenced by a seeming preference for seaweed sheets sources from various species as a flavouring agent, as a meal or snack in itself, or as an accompaniment to other foodstuffs. In reality, seaweeds actually have a long and varied history, with the earliest possible usage of the organisms dating back to before recorded history. It can be surmised that many foraging societies which lived off or near coastal regions may have consumed seaweeds as a type of food, or as an accompaniment to other types of nutriment. The organisms (then considered as plants) were not at all unknown to the Early Greeks, although there was a varied preference for it. Seaweeds were also consumed by various coastal European societies, and were not at all unknown to the Icelanders and the Norwegians who had a strong seafaring culture. The coastal regions of France was home to various soup-based dishes based on or containing seaweed, while regions in Ireland, Wales, and South West England have employed seaweed as food and medicine since before recorded history, with the practice of consuming seaweeds not at all alien to the Celts, the Teutons, and the Bretons, although the practice was by and large not as pervasive as seaweed consumption is today when compared to scale.

In the Americas, prior to the eventual colonisation of the continent by Europeans, various Native American first peoples have been wildcrafting and even unconsciously cultivating seaweeds for food. For the Huron, Haida, and Alonquin First Peoples nations, pond or lake-based and ocean-based seaweeds served as food. Coastal tribes wildcrafted seaweeds, while tribes near lakes or large rivers gathered them whenever in season. Some tribes, especially those near Lake Chad (a long and storied source for seaweed and other water-based foodstuffs for First Peoples) referred to it as dihe, although the term is more often used to describe spirulina than other forms of seaweed. [3] In Asia, where the consumption of seaweed is considered at an all-time high, Chinese peoples have long wildcrafted and later cultivated seaweed for food and medicine, a practice, it is believed, that later spread to Japan, and eventually to Korea. It can be assumed that the Chinese first began consuming various types of seaweed sometime in the Second or Third century B. C., a practice that later spread to the primitive Japanese peoples such as the Ainu, and that later prevailed as a general practice throughout the Japan by as early as the Jomon Period (circa 14, 500 - 12, 000 BC). Kelp species were perhaps the earliest forms of wildcrafted and later, cultivated, seaweeds, although in the coastal areas of the Philippines, seaweeds such as dead man's fingers, sea grapes, and even the excreta of various sea animals such as sea-urchins and sea slugs (erroneously but traditionally said to be a type of 'seaweed') have long been consumed more often than not in its fresh state by a number of coastal or sea-faring tribes outside of any external influence from other seaweed-consuming peoples - a practice that would later be enhanced by the eventual introduction of Spanish cuisine via the colonisation of the Philippines. Seaweeds were not an unknown food-product even in India, although its consumption as a type of food was at best rare.

Because seaweeds readily decompose and (until preservation introduced by modern methods) do not keep well if stored for long periods, there is very little extant evidence as to exactly what types of seaweeds were consumed by primitive societies and how exactly they were prepared, with the exception of the Chinese and Japanese methods of consumption and preparation, as well as the production of Irish moss or carrageenan, also a well-documented practice. Prior to the introduction of modern preservation methods and industrialised cultivation, seaweeds were almost always consumed fresh, or at least no more than a day or two old. Later, seaweeds came to be dried, and trading inland to non-coastal areas became possible. It should be noted that the dried seaweed of ancient times is nothing close to the kind of dried seaweed (i. e. kombu or nori) made available today, but were still highly perishable goods that needed to be used as soon as possible lest they spoil.

Seaweeds make for highly nutritious foodstuffs, with their medicinal applications going hand-in-hand with their culinary usage (i. e. food as medicine). As of today, seaweeds still play an integral role in various forms of cuisine, although they are more often employed as food supplements in capsule, powder, or tablet form more so than as food-proper in the West. In Asia, seaweeds are still employed strongly (if not chiefly) for food, although some individuals now integrate it into their daily diet more for medicinal reasons than for gustatory ones (the latter being the norms of the past). Unlike prehistoric seaweed gathering, most of the seaweeds made available in the market today are cultured in highly controlled environments to ensure the utmost in safety and sanitation, although it is suggested by a few gourmands that wildcrafted seaweeds are by far more 'superior' to cultured ones flavour-wise. Seaweed culture can be done in coastal areas or in areas near lakes with very little raw material required, although man-made ponds and controlled environments, with seaweeds cultured from 'starters' are also known. In areas like Japan, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines the culture of saltwater or freshwater seaweeds is something of a cottage industry, although Japanese seaweed culture is by and large more refined than the latter two. It is surmised that at present, the largest seaweed-producing industries are those that cultivate kombu, nori, and wakame seaweeds in Japan, the Philippines and South East Asia in general, and some areas of Europe and the Americas.

Seaweed - Herbal Uses

Since prehistoric times, seaweed has been employed for a number of different purposes, the most common being as a type of food or as a condiment or additive to food. Seaweed is popular in regions that have ready access to the ocean, although it is also known to be consumed on settlements or societies that live close to large bodies of freshwater. Seaweed can be employed as a type of 'vegetable' and incorporated into soups, stews, and soup-based dishes. When dried and crumbled, or otherwise powdered, it can be employed as a type of 'spice' or as an alternative to salt thanks to its rich iodine content. Seaweeds can even be dried, toasted, and eaten by themselves as a type of snack, or otherwise pureed and made into or incorporated into beverages. As of recently seaweed has been used as a type of food supplement, or as a healthy alternative to sodium, and as a 'whole food', often marketed in the form of powders, capsules, or tablets. Depending upon the society or culture that consumes seaweed, there are any numbers of various preparations for it, all of which usually revolve around its use as a type of food.

In Asia, where seaweed is a highly popular foodstuff, it comes in a variety of preparations. There seems to be a uniform type of seaweed for both Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cuisine characterised by either whole dried (and later reconstituted or rehydrated) seaweed fronds employed either as a base for soup stock (as is the case for kombu and wakame) or thick / thin sheets of seaweed used as a wrapper for rice and other foods, or as a snack in its own right (as is the case for nori). While Chinese cuisine focuses mainly on using seaweed as a soup or stock base, or otherwise as a fresh salad, Japanese cuisine has somewhat refined the employment of seaweed to incorporate it in nearly everything. Kombu [4] and wakame [5] seaweeds are popular bases of soups, stocks, and stews, but are edible seaweeds in its own right. Perhaps the most popular type of Asian seaweed 'preparation' is nori [6] - thin to slightly thick sheets of green to slightly purplish seaweeds used to wrap rice balls (onigiri), sushi, and maki rolls (at least on the inside). Either of the three can also be used as a condiment or flavouring. In the case of nori, it can be shredded or powdered and employed as rice sprinkles (furikake), or otherwise roasted (yaki nori) prior to use, or roasted, flavoured and cut into chips to be eaten as a snack (ajitsuke-nori) - a practice that would later spread to Korea in the form of gim and miyeok.

Seaweeds contain significant amounts of iodine and is thus an excellent source of iron. It is also noted for its slightly salty to sweet-salty taste (depending on the type of seaweed), and thus makes for an excellent alternative to salt. Seaweeds contain varying amounts of trace vitamins and minerals, as well as being chock-full of beneficial enzymes that encourage the growth of good gut flora. In Japan, Korea, and China, seaweed-based dishes are eaten as appetisers or course-finishers, and may be consumed during the summer months as part of a nutritious and filling meal, or during the winter months in the belief that it staved off colds and fevers. The nutritional density of seaweed as well as its preparation into filling, hearty, and warming foodstuffs, or as highly nutritive cold foods have spawned the belief that it is able to cure various bronchial disorders, among them colds, cough and flu, as well as other diseases such as fevers. Its rich iodine content makes it excellent for staving off iron deficiency in both children and adults, while its trace mineral compounds provide a readily bio-available source of micronutrients that make up a basic balanced diet. Studies have shown that people who consume a lot of seaweed have healthier gut flora than individuals who do not. Because of its nutrient density, seaweeds are a staple meal for expectant and lactating mothers, as it is believed to help with the development of the foetus and the prevention of various deficiencies that may lead to abnormal or impaired growth. Seaweeds like wakame have also been shown to possess significantly bio-available amounts of omega-3 fatty acids, as well as a unique compound called fucoxanthin which helps to increase overall metabolism and encourage fat burning. In Chinese Traditional Medicine, Korean herbal medicine, and Japanese kampo alternative medicine, seaweeds have also been used to purify the kidneys and improve intestinal health, as well as encourage the regeneration of hair and skin.

In the Philippines, seaweeds are consumed all year round, although the types of seaweeds consumed varies and differs greatly from the ones consumed by the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans. Seaweeds such as dead man's fingers (locally called guso) [7] and sea grapes (locally referred to as lato) [8] are very popular seaweeds, generally eaten 'fresh from catch' with only a light rinsing of warm water and a little seasoning of vinegar or fish paste added for flavour. It is usually prepared into a fresh 'sea salad' accompanied by sliced tomatoes and cucumbers, although it can also be integrated into soups and hearty stews. It is a staple in some areas of the country for fish-based stocks or broths, and is believed to be highly nutritious. It is given to pregnant and nursing women in the belief that it helps the development of the foetus, and, during nursing, that it fortifies the breastmilk and increases milk production. A soup with either types of seaweed added is often consumed during the onset of a flu or fever, or during the monsoon seasons to help stave off the disease. It is given to children in coastal areas to treat iodine deficiency and rickets, while women and young teens consume it during menarche to prevent anaemia, goitre and to treat dysmenorrhoea. Seaweeds like dead man's fingers and sea grapes are an excellent source of trace vitamins and minerals, and, like wakame and nori are also an excellent source of calcium and niacin, as well as trace micronutrients.

In the Western sphere, several species of seaweed are consumed as food, with the most popular being laver, carrageen (aka Irish) moss, sea lettuce and bladderwrack. It must be noted that laver (Porpyhra umbilicalis) comes from the same species as Japanese nori (Porphyra yezonsi), and is employed medicinally for nearly the same purposes as nori, with only the preparation that varies. Unlike Japanese nori which is made out into dried sheets, laver is often employed in its raw (i. e. unprepared) state, and is boiled for several hours until it forms a gelatinous mush that is said to keep for a week. This preparation yielded a thick, porridge like substance called 'potted laver' that was popular during the 18th century. Laver can also be used as-is, typically heated and made into a salad, usually with a side of rashers or bacon, or otherwise consumed as a cold-cut salad accompanied by cuts of lamb or mutton. It can be delicately flavoured by adding the juice of lemon and consumed while fresh, or when slightly heated. In Wales, it is often made into a delicacy called laverbread which is composed of boiled or potted laver, rolled with whole oats or oatmeal, and then pan fried or deep fried prior to serving. Laver contains high proportions of protein and iodine, as well as being an excellent source of B-vitamins (B2 specifically), and vitamins A, C, and D, making the regular consumption of laver an excellent means to prevent various vitamin deficiencies. As with nori it was given as a nutritive and filling meal to pregnant women, but also to convalescent individuals and the elderly in the belief that it helped to boost their health. [9] Another type of popular seaweed is called Irish moss (Chondrus crispus), a species of red algae that grows abundantly in select areas of Europe and North America. Long cultured and favoured by the Irish and Scottish who refer to it as carrageen, it is employed as a culinary additive and functions as a thickening agent in various products such as ice cream and custards. Added to meats, it acts as a binder, and can be found in various Irish or Gaelic preparations for luncheon meat.

In Scotland, seaweed is made into a beverage by boiling it in milk and adding flavouring agents such as vanilla beans, cinnamon, whiskey, or rum, resulting in a jelly-like substance that is both filling and nutritive. The most popular use for Irish moss is as a fining agent for the brewing of ales and other types of beer - a practice that has been adopted by various home brewers and craft breweries of late. Like laver, Irish moss is high in protein and trace minerals as well as vitamins, and preparations of the milk-carrageen beverage is often given to convalescent individuals to hasten recovery, or otherwise fed to very ill persons, especially children. It is believed to be an excellent pick-me-up drink, partaken of just before the onset of illness to prevent the worsening thereof. [10] A similar species of seaweed known as carragheen or carragheenan (not to be confused with the compound derived from Irish moss) comes from the Mastocarpus stellatus, and is employed for nearly the same purposes as Irish moss, although it is rarely used for the refining of beer. It is prepared, much like Irish moss, into a beverage reputed to stave off the flu, cure the common cold, and remedy coughs and fevers. [11]

A now somewhat rare type of edible seaweed known as sea lettuce (varies, all from the genus Ulva) is farmed or wildcrafted and used in its fresh state as an ingredient for soups and hearty stews. It is often given to individuals who suffer from flu, or to very young children as it is an excellent source of protein, iron (to counteract anaemia), soluble dietary fibre, and high amounts of other vitamins and minerals. [12] Another well-known and much employed variety of seaweed is called bladderwrack and is sourced from the Fucus vesiculosus. Commonly found in the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, it resembles a multi-leafed plant, the whole of which can be dried and consumed as a salad, or otherwise powdered and employed as an additive to food. Bladderwrack was employed for a time as an alternative to sea salt and is today experiencing resurgence as a 'healthy' seasoning. Like other seaweeds, is it high in iodine and is excellent for combating anaemia and goitre, and is even believed to help stimulate and detoxify the kidneys. Bladderwrack may have perhaps even been used to treat open wounds, either as an early type of 'plaster', or, if decocted, as a rinse that helped to promote healing and prevent infection, although this practice is no longer common today. [13]

Seaweed - Esoteric Uses

With a long history of use, seaweed has also been thought of by ancient peoples as possessing magickal properties. While there are various traditions (all depending on the culture) regarding the magickal use of seaweeds, Western lore suggests that it is an excellent means to summon the elements of the sea and of water in general (undines), simply by offering a piece of seaweed into a body of water and calling forth the elementals. It was believed that seaweed could call forth the wind, and Early Greek sorcerers would whip a strand of seaweed above their heads clockwise while whistling in the belief that it called forth the winds - a practice that persisted until well into the High Middle Ages and the Dark Ages as a 'spell' that was said to conjure up a storm. Because it was a product of the sea and was in itself 'briny' or salty, it was said to deter evil spirits. Braids of seaweed were hung outside the doorposts of coastal areas to prevent bad luck and drive away evil, while ships were sometimes festooned with braided seaweeds to ensure a safe voyage. In sympathetic magickal practices and folk magick, a jar filled with seaweed and some whiskey, when placed in a kitchen window, was said to promote good luck and a steady flow of money in business. [14] Carrying seaweed upon one's person was also said to ward off demonic or evil entities, and, in Filipino shamanic magick, braids of seaweed tied to a staff or hung upon an entrance served as deterrents for goblins, demons, fell-beasts and their ilk.

Seaweed - Contraindications And Safety

While seaweeds are generally safe to consume in moderate to slightly large dosages, the overconsumption of seaweeds or products containing some types of seaweeds such as laver, bladderwrack, or wakame may result in iodine poisoning and vitaminosis. It should also be noted that some species of seaweed are poisonous, or, if a batch of seaweed has been affected by red tide poses a very great risk to health. Some types of seaweeds may even contain inordinately high amounts of heavy metals such as mercury or lead that may lead to various sorts of poisoning. It is advised that seaweed consumption be moderated, and that only reliable sources for clean, preferably organic, cultured seaweed, be opted for in lieu of the supposedly more flavourful albeit less secure wildcrafted types.

Seaweed - Other Names, Past and Present

Chinese: zicai / haicao / kunbu / guanbu (the latter two believed to be the original Japanese

kombu) / qundai cai (Chinese name for wakame)

Japanese: nori (Porphyra yezonsi) / wakame (Undaria pinnatifida) / kombu (Saccharina

japonica / Saccharina latissima [all three are various preparations of seaweeds from various / similar seaweed types]

Korean: gim / kim (similar to the Japanese nori) / miyeok (Korean name for wakame)

Hindi: samudri sivara / samudri sivar

French: algue

Italian: alga marina

Spanish: alga

Filipino: guso (dead man's fingers, Codium fragile) / lato (sea grapes, Caulerpa lentillifera) /

lukot (not exactly seaweed proper, but the secretions (excrement) or eggs of a sea slug known as the 'Sea Hare'; Dolabella

auricularia / Aplysiomorpha) / damong-dagat (lit. 'sea grass')

Welsh: laver (Porphyra umbilicalis)

Irish: carrageenan / carrageen moss (Chondrus crispus) / carragheenchluimhin cait (lit. 'cat's

puff'; Mastocarpus stellatus) / dulse [types / species of seaweed locally harvested and prepared in Ireland]

English: laver / seaweed / dead man's fingers / sea grapes /

bladderlocks (Alaria esculenta) / bladderwrack (Fucus vesiculosus) / chlorella (Chorella) / oarweed

(Laminaria digitata) / sea lettuce (sourced from various species of Ulva); various other species of seaweed

German: algen

Greek: fyki

Latin (esoteric): agla

Latin (scientific nomenclature): various, but generally Porphyra yezonsi / Undaria pinnatifida / Saccharina

japonica / Saccharina latissima / Codium fragile / Caulerpa lentillifera / Porphyra umbilicalis /

Chondrus crispus (other scientific nomenclatures for respective seaweed varieties stated above)

References:

[1][2][3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seaweed

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kombu

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wakame

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nori

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codium_fragile

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caulerpa_lentillifera

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laver_(seaweed)

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chondrus_crispus

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carrageen_moss

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_lettuce

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bladderwrack

[14] https://www.janih.com/lady/herbs/magick/B.html; https://www.oocities.org/samual53115/herbs/magical-properties/kelp.htm

Main article researched and created by Alexander Leonhardt.

© herbshealthhappiness.com

Infographic Image Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Umibudou_at_Miyakojima01s3s2850.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boiled_wakame.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kombu.jpg

(Creative Commons)

1. Famous Chef Sheds 60lbs Researching New Paleo Recipes: Get The Cookbook FREE Here

2. #1 muscle that eliminates joint and back pain, anxiety and looking fat

3. Drink THIS first thing in the morning (3 major benefits)

4. [PROOF] Reverse Diabetes with a "Pancreas Jumpstart"

5. Why Some People LOOK Fat that Aren't

6. Amazing Secret Techniques To Protect Your Home From Thieves, Looters And Thugs

7. The #1 WORST food that CAUSES Faster Aging (beware -- Are you eating this?)

If you enjoyed this page: