Sumac

Sumac Uses and Benefits - image to repin / share

Infographic: herbshealthhappiness.com. Image credits: See foot of article

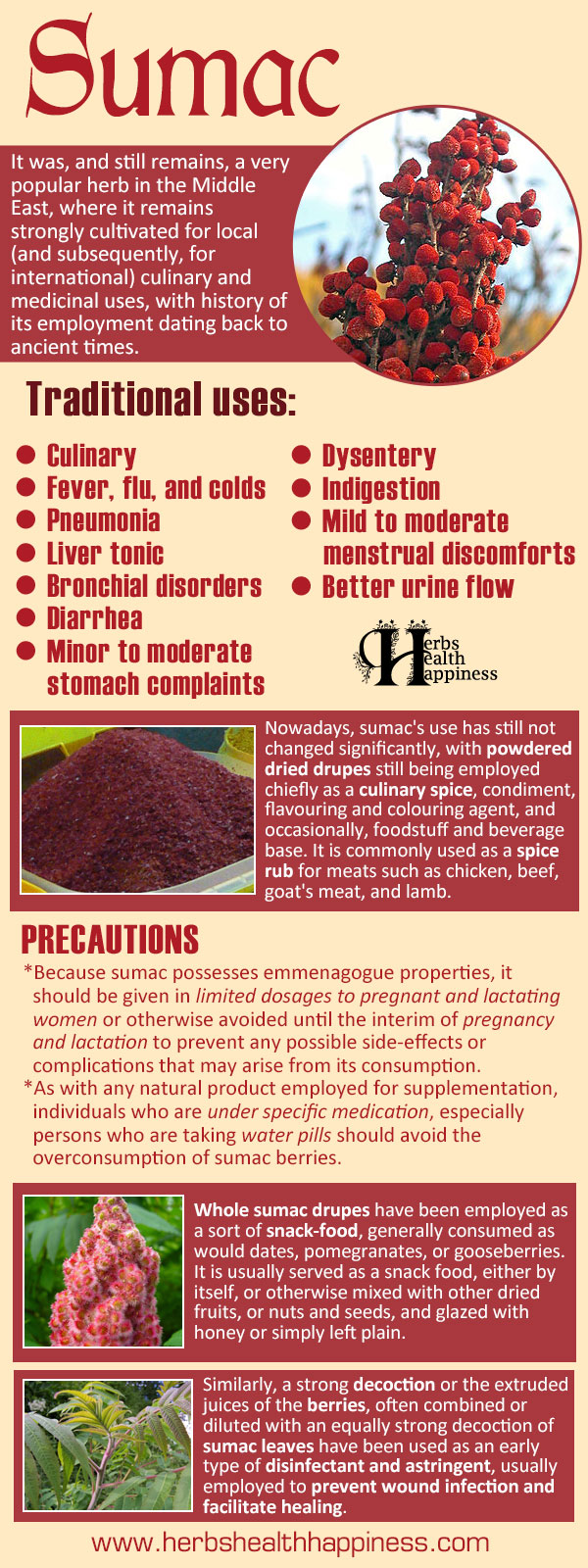

Sumac - Botany And History

Sumac is a species of flowering plant from the genus Rhus, the fruits (and sometimes even the flower petals) of which chiefly cultivated and largely used as a culinary spice, flavouring agent, colouring agent, food, and condiment in Arabia and its surrounding areas. This semi-annual plant, readily recognizable by its brightly coloured and somewhat standoffish inflorescence was initially wildcrafted, and later on cultivated in sizeable numbers. It was, and still remains, a very popular herb in the Middle East, where it remains strongly cultivated for local (and subsequently, for international) culinary and medicinal uses, with history of its employment dating back to ancient times.

Sumac belongs to a broad genus of plants, with more than two hundred different varieties all throughout much of the world. It is usually passed off as a toxic or dangerous plant, and is mistaken for the poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) which is not at all related to true sumac. Because of this case of 'mistaken identity' most Western culinary and alternative medicinal practices often steer clear from the usage of true sumac. Older herbals generally confuse poison sumac and true sumac simply because the former was originally referred to as Rhus vernis, and was thought to be a relative of Rhus coriaria and its other varietals, up until the 1900s, where it was recast as Toxicodendron vernix, and its true genus properly identified. Some botanical manuals and schools of alternative medicine still believe, however, that poison sumac is distantly related to true sumac, and thus perpetuates the undue fear of the usage of sumac.

True sumac, like poison sumac, is a medium-sized shrub which can grown to the size of a small tree (usually one to ten metres) if left to its own devices, with pinnate, semi-gloss, often broad compound leaves that are arranged asymmetrically, although some sumac species have simple leaves or trifoliate leaves and are arranged spirally throughout its branches. The plant is highly distinctive for its moderately sized red drupes or berries, which grow in clusters on the tips of the uppermost stems of the tree or shrub. It is also highly discernable for its unique inflorescence, which, in spite of being subtle, can be somewhat gaudy especially while in bloom. The flowers are noted for its variances in colouration, with some species sporting ivory-hued flowers, some jade-hued, although the most popular species sport the maroon and vermillion-hued inflorescences which are most commonly found throughout much of the Middle East, some parts of the New World, and a sizeable part of the Mediterranean. Due to the sheer size of the genus Rhus several kinds of sumac have been employed both for culinary and medicinal purposes over the ages, with each distinct variety possessing its own unique properties, along with similar properties that it shares with its relatives. [1]

Sumac has been used since time immemorial as a foodstuff, a culinary spice, as medicine, and as a source of other articles or a base for a number of different products, although its usage chiefly depended upon its varietal and sometimes even upon the culture or society to which it has been made available. During ancient times, nearly all varieties of sumac (including the then assumed-to-be-related poisonous ones), were employed in the creation of products that make a strong impact on the art and aesthetics of many a country. To this day, sumac is still employed for the creation of items for artisanal use, although its primary use still veers more strongly towards the culinary world. [2]

Sumac - Herbal Uses

Many varieties of sumac (i. e. smooth sumac, Rhus glabra; staghorn sumac, Rhus typhina; and fragrant sumac, Rhus aromatica) are chiefly used as a type of foodstuff, and, more popularly, as a culinary condiment known for its striking vermillion or red colouring, and its popularity in Middle Eastern, and some branches of First Peoples cuisine. Aside from its long-standing use as a snack food by many early nomadic cultures in both the East and West, it drupes have also been employed as a primary ingredient in a number of beverages, with examples of the product being present in many Native American tribes, Bedu groups, and even moderately sizeable to large communities in various parts of the globe. Prior to the advent of the modern age, sumac was also wildcrafted or otherwise harvested and stored as famine food by many native cultures, or simply consumed as a type of snack as would any other berry or fruit. It is the Middle East which be credited for creating one of the most popular culinary uses for sumac, for they were among the first (but not the only) culture who first used the drying and grinding process to create a richly pigmented, highly aromatic, and very astringent condiment that is to this day used in a majority of Middle Eastern and Eurasian foodstuffs. It should be noted however that the Native Americans also employed a similar process of drying and powdering sumac and using it as a condiment, flavouring, food colouring, and early preservative agent for foods. Cultures which have employed sumac may have thought about the drying and powdering for the purposes of extending the usefulness of the plant's fruit even long after the fruits were out of season, creating the earliest emergency rations, which were pretty commonplace for a number of aboriginal societies. [3]

Nowadays, sumac's use has still not changed significantly, with powdered dried drupes still being employed chiefly as a culinary spice, condiment, flavouring and colouring agent, and occasionally, foodstuff and beverage base. It is commonly used as a spice rub for meats such as chicken, beef, goat's meat, and lamb. Powdered sumac drupes can even be employed as a spice for soups, stews, and even sweetmeats and a number of Middle Eastern desserts. [4] Aside from its powdered form, whole sumac drupes have even been employed as a sort of snack-food, generally consumed as would dates, pomegranates, or gooseberries. It is usually served as a snack food, either by itself, or otherwise mixed with other dried fruits, or nuts and seeds, and glazed with honey or simply left plain. [5] Whether consumed whole or employed as a culinary spice, sumac can be employed medicinally for its emmenagogue, diaphoretic, diuretic, and cooling properties. It is usually consumed as a ready snack to remedy the first onset of fevers, to alleviate mild to moderate menstrual discomforts, and to remedy incontinence and help to improve the better elimination and flow of urine and the elimination of excess bodily fluids due to its diuretic properties. Furthermore, folkloric medicine suggests that sumac may possess memory-enhancing properties when consumed on a regular basis, typically as a snack, usually in its whole form, although such a claim cannot be fully substantiated by modern medicine. [6] Aside from these medicinal properties, the fruit of the sumac plant is also thought to be a highly cooling foodstuff, making it an excellent (if not choice) snack during the summer months. It is because of its innate cooling ability that the fruits of the sumac is preferred as a flavouring and prime ingredient for beverages, usually by employing a slow maceration process which imbues plain water with the essence of the fruit, or through the integration of the whole flesh of the fruit (sometimes necessitating the need for labour-intensive separation of the flesh of the fruit from the seeds and the piths) into a puree or shake which is then consumed in either its pure or chilled form, (usually as a pure substance), or otherwise as a concoction composed of other fruits, some herbs, spices, and often natural sweetening agents. [7]

Employed by itself as a foodstuff, a beverage-base, or as a condiment and spice, sumac possesses a slightly tangy tartness reminiscent of lemons or tangerines that brings out the flavour of a number of different foodstuffs and adds a zing to beverages when used even in minute amounts. During the time of the Early Romans, sumac was employed as a souring agent in lieu of vinegar, either by drying the astringent fruits and reducing the whole dried mass into powder, or by otherwise macerating the whole fruit is water and extruding the rich, red, and very sour liquid which would have then be employed as an early type of vinegar. [8] The extruded liquid may be employed as more than just a flavouring agent or condiment, as it has been used by ancient peoples such as the Native Americans, Early Romans and perhaps even the Early Greeks as a prototype antiseptic and disinfectant, perhaps inspiring the later employment of wine and alcoholic spirits for similar purposes. It has even been assumed that the dried and powdered fruit of sumac has been employed by early First Peoples for recreational purposes, either by itself or mixed with other herbs and smoked in pipes, although this may have been done more for attributed curative properties or for esoteric purposes, more so than for any hallucinogenic effect or purpose. [9] It may have been employed medicinally to treat bronchial disorders, although this supposition is not backed up by traditional usage.

Sumac berries, whether dried and powdered or otherwise consumed whole, have been employed to treat a number of different diseases, although due to its cooling properties, it was usually employed for the treatment of fevers, flu, colds, and even pneumonia, usually when combined with other therapeutic herbs. In the Middle East, dried and ground sumac berries were often incorporated into a spice mixture known as za'atar, which was employed as a seasoning spice and condiment. Za'atar is also highly valued by other cultures such as that of India for its therapeutic and nutritional properties, and may even be taken as a daily supplement in either through the simple integration of the spice-mix into any assortment of foodstuffs, or via direct consumption of the substance is whole or diluted form. [10] A decoction of the dried berries or berry powder, or otherwise a slow cold infusion of the fresh fruits, when sweetened with honey, jaggery, or molasses can be made into a syrup to treat bronchial disorders, or consumed as a beverage to treat dysentery, diarrhoea, indigestion, and other minor to moderate stomach [11] complaints and can be drunk or otherwise consumed as an aperitif to facilitate in digestion and the overall absorption of nutrients from meals - a practice which is common in a number of Middle Eastern cuisines. In Native American folkloric medicine, the berries are even employed as laxative and are to this day employed as a hepatic tonic (liver tonic) and detoxification aid, especially when combined with spices such as cayenne pepper, paprika, garlic, and turmeric (the latter spices being modern additions to a traditional recipe). [12] Similarly, a strong decoction or the extruded juices of the berries, often combined or diluted with an equally strong decoction of sumac leaves have been used as an early type of disinfectant and astringent, usually employed to prevent wound infection and facilitate healing. It's usage as a curative astringent liquid can be traced to the Iroquois, the Chippewa, and the Navajo First Nations, who used decoctions of both the berry and leaf to treat arrow wounds and other physical injuries brought about by hunting or warfare. [13]

Sumac berries have also been employed as the primary constituent of some candles and stick incenses, particularly candles that were produced in Japan during the Tokugawa and Meiji Eras, as it yielded a flammable wax (actually a type of solidified ester) which was a byproduct of traditional Japanese lacquer making. The wax was gathered, melted down, and moulded into candles which was known for being smokeless and slightly fragrant, and was evidently more superior to beeswax or lard-based candles that were more prolifically used during those times. [14] Because of its slightly fragrant nature and vastly superior burning properties, such candles were often reserved for sacred uses in temples and home altars, although more affluent individuals such as those who belonged to the aristocracy also employed the candles for more utilitarian purposes. Powdered sumac could even be mixed with other fragrant resins or spices and stuck into thin bamboo sticks or otherwise moulded into balls or other shapes. During earlier periods, it may have even been burnt as loose incense over coals, along with other fragrant resins and spices.

Nowadays, sumac berries are often consumed as a type of food supplement, or otherwise eaten as part of trail mixes, if not simply as snacks. Some species of edible sumac such as the Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) is highly valued for its very potent antioxidant properties. It is often sold whole in health food stores and grocery aisles, or otherwise found in encapsulated whole form, or extracted capsule form in drug stores and alternative medicine stores.

The bark of the plant itself has been used by Native Americans as an emmenagogue and as an early type of dyeing agent for both leather and cloth. Because of its tannic nature, it not only helped to soften untreated hides, but also made for an excellent darkening dye which worked especially well for rough-spun fibers. In earlier times, sumac played a very integral role in the creation of the famed Morocco leather, which is known the world over for its suppleness and esteemed quality. [15] This self-same dyeing capacity also allowed sumac bark to be employed as a type of ink in much the same vein as the traditional iron gall ink by simply combining iron(II) sulfate and sumac bark, or, alternatively, dried sumac berries. [16] Long strips of sumac bark were even employed by many tribes for the creation of baskets, or, when threshed and beaten into thin strips and woven, was used as a type of 'fabric' used to decorate articles of clothing or create an assortment of accessories.

Sumac - Esoteric Uses

Sumac in its various constituent forms have been employed for esoteric purposes since ancient times, with the earliest usage dating back to the First Peoples of America, which often employed the dried berries and leaves of the plant as a smoking mixture, usually by itself or in combination with other smokable herbs in their sacred rituals. It can be classified as a type of kinnikinnick, although strictly speaking, 'true' kinnikinnick is chiefly composed of red willow bark, sometimes combined with wild tobacco. It can be smoked in calumet (accurately referred to as chanunpa) pipes (Peace pipes), or otherwise burnt as a type of smudge in earthenware bowls. It is believed by many shamanic cultures that sumac smudge made from its dry berries, its bark, or its leaves help to not only cleanse an area of negativity, but to invite good fortune, as well as to appease spirits. Some Native American tribes believe that the smoke given off by smudge constituted from (or that contains) sumac helps to facilitate harmony and serve as a reminder of one's oneness with the whole of creation. It is due to this belief that most modern esoteric applications for sumac suggest it as an excellent herb for resolving conflicts and facilitating harmony. [17]

In the Voodoo and Hoodoo traditions, sumac berries, bark, and leaves (or oftentimes a combination of all of these constituent parts) are commonly encased in medicine pouches or juju bags and employed as a type of amulet that is said to ward off bad luck. It is often carried by individuals who face court cases, as it is believed that keeping a pouch of sumac berries close to one's person while undergoing a legal debacle will invariably help in winning the case, or at least lessening the severity of a sentence. In the Hoodoo systems of magick, it can be infused in water along with other herbs to create holy water in a similar vein to Florida water, often employed for blessings, cleansing, or as an offertory item. [18]

In more traditional shamanic systems of magick, the branch of the sumac plant has long been a prime choice for the creation of calumet / chanunpa pipe stems. It was traditionally soaked in fat, which was absorbed by the soft, spongy pith found in its inner center. Maggots were then introduced into the stem and sealed in, allowing the small creatures to eat the fat-infused material. When the whole of the pith was eaten through, it was then cleaned and decorated, with the carved pipestone head (usually of catlinine, but may be made from an assortment of other materials) integrated much later via a Blessing and dedicatory ceremony to both Wakan Tanka (The Great Mystery), and White Buffalo Calf Woman. [19]

Sumac - Contraindications And Safety

While a number of species of sumac are generally safe to consume orally or otherwise apply topically, sumac may often be indistinguishable from poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), which can cause any number of uncomfortable to potentially lethal side-effects if accidentally applied topically or otherwise consumed orally. Because of this, it should be noted that one should purchase sumac berries and all its constituent parts solely from reliable sources. Any attempts at wildcrafting sumac berries should be done with the aid of a professional bushman, although as a general rule of thumb, Rhus vernix and all its related edible species typically possess a mild down on its fruits, while the non-edible varieties typically appear smooth-skinned.

Because sumac possesses emmenagogue properties, it should be given in limited dosages to pregnant and lactating women or otherwise avoided until the interim of pregnancy and lactation to prevent any possible side-effects or complications that may arise from its consumption. As with any natural product employed for supplementation, individuals who are under specific medication, especially persons who are taking water pills should avoid the overconsumption of sumac berries. Care should be taken when partaking of very strong decoctions of any of its constituent parts for more than a week, with anything beyond a weekly treatment necessitating the assistance of a professional herbalist to ensure safety.

Sumac - Other Names, Past and Present

Japanese: urushi

Korean: ochnamu

Hindi: dansi / dansara / darsan

Malayalam: chippamaram

Arabic / Syrian: summaq / summaqa (lit. 'red'; etymological origin)

French: sumac

Old French: sumac

Italian: sommacco

English: sumac / sumach

Mediaeval / Esoteric Latin: sumach / Indian salt

Latin (scientific nomenclature): Rhus coriaria / Rhus aromatica (other nomenclatures exist, depending on the specie and

varietal)

1. Famous Chef Sheds 60lbs Researching New Paleo Recipes: Get The Cookbook FREE Here

2. #1 muscle that eliminates joint and back pain, anxiety and looking fat

3. Drink THIS first thing in the morning (3 major benefits)

4. [PROOF] Reverse Diabetes with a "Pancreas Jumpstart"

5. Why Some People LOOK Fat that Aren't

6. Amazing Secret Techniques To Protect Your Home From Thieves, Looters And Thugs

7. The #1 WORST food that CAUSES Faster Aging (beware -- Are you eating this?)

References:

[1][2][3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumac

[4] https://www.woodherbs.com/Sumach.html

[5] https://voices.yahoo.com/sumac-spice-uses-middle-eastern-cuisine-health-486369.html?cat=22

[6] https://firstways.com/2011/08/23/how-and-why-to-eat-sumac/

[7] https://www.eattheweeds.com/sumac-more-than-just-native-lemonade/

[8] https://nativeplants.evergreen.ca/search/view-plant.php?ID=00566

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinnikinnick

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Za'atar

[11][12][13] https://www.aihd.ku.edu/foods/smooth_sumac.html

[14] https://www.bonnymans.co.uk/products/product.php?categoryID=1399&productID=6408

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morocco_leather

[16] https://www.flickr.com/photos/lavonasherarts/2988918705/

[17] https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=YXoOye0jcvkC&pg=PA93

Main article researched and created by Alexander Leonhardt.

© herbshealthhappiness.com

Infographic Image Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SumacFruit.JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sumac.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sumac-Drupes.JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rhus_typhina.JPG

(Creative Commons)

If you enjoyed this page: